An Excerpt:

An Excerpt:When I was a kid I used to love riding my bike through the quiet suburban streets of North Star, Delaware. Down Jupiter Road, turning right onto Venus Drive, left on Pluto Street, then dumping my bike and running, hair flying, eyes tearing, into the tall corn fields, hiding and chasing and spinning dizziness into the dirt, my laughter bouncing across the hot, sticky air. In those moments, when it was just the woods, fields and meadows of my childhood, and me I could forget about feeling lost. I found safety in disappearing into the earth.

I loved to sway from the tire swing that hung out back by the creek from the ancient oak tree. Yet, what I wanted most was to be pushed & to feel hands on my back, and whoops of encouragement. I wanted the attention of my mother or father or either of my brothers, wanted to feel eyes on me, lovingly watching me. Instead I ran across the land surrounding our development, not allowing myself to feel afraid, not knowing how to sit still or how to observe the movement within my body. I thought that if I kept moving I would be safe.

On a balmy spring day in 1967, the year I turned eight, my best friend came to my house with a gift box in her hand and a mischievous look in her eye. Teal, who had a pixy haircut like mine and was dressed like a boy, handed me the box, urging me to open it. I felt it shake and skitter, and tore off the wrapping with intense curiosity. Inside, in a nest of cotton balls and grass, was a tiny duckling that peered out at me with a tilted head, as if to say, so, what’s it gonna be? I picked him up and held him to my neck, feeling an instinctual urge to feed and protect him.

This is for me?

I thought you’d like him. Isn’t he a cutie? she said, reaching to pet him. I hope it’s okay with your parents.

I love him, I said, looking up at her with gratitude I didn’t know how to express. He’s so soft.

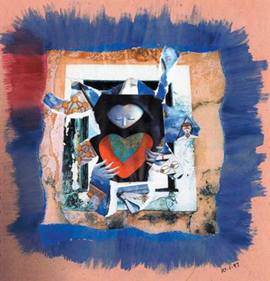

Louie, as I came to call him, was an Easter cast-off, an orphan. I took to my new role of being his mother with extraordinary pride, holding him on my lap, stroking his pale yellow down, bathing and feeding and walking him around our spacious property. I felt like I had a place in the world, a purpose, like I belonged to someone.

We were not a very skilled family when it came to caring for others; children and animals were best left to explore their environment on their own. I learned quickly how to put on Band-Aids and what to do if I stepped on a bee, yet had no idea how to handle the taunts and teasing of neighbor children.

In my house you had to fend for yourself. With no one to teach how the world worked, I made things up. I made judgments, observations and developed strong opinions. I became an authority on everything, based on imagined feelings and reactions. I taught myself how to look out for my friends, but never learned to do this for myself. I was trusted to know what I needed, even when I didn’t have a clue. Thus, from a very young age, it was up to me to determine if I needed a coat, if it was safe to play on a construction site, if I was capable of diving into the deep end of the pool. My parents believed that the simple act of growing older would teach me all I needed to know. Rules didn’t exist. There was no sitting at the table until midnight until I ate my peas, no getting grounded, no moral lectures. No rules, no consequences, no conflict. It was up to me to figure out who to trust, as if trust were innate rather than earned.

Even at eight, I knew there was something vitally wrong about all this. I threw myself into caring for my duckling with complete passion and determination, as if to prove that I already knew everything about being a mother, as if my mother might see what I wanted from her and rush to follow suit.

Louie grew quickly in the 20 x 20 pen we made in what used to be my mother’s vegetable garden. His soft down gave way to smooth white feathers, and his beak grew long and yellow. It took all of my eight-year-old strength to pick him up. I unburied the doghouse we’d used for the puppy we brought home from the Humane Society the year before, cleaned it off and put it in the pen with Louie thinking he’d enjoy the shelter it provided. The doghouse served only as a launching pad for flight training.

I took it upon myself to teach Louie to fly, believing that my little duck would need this skill in order to survive. My younger brother and I would lift him up onto the roof and then one would hold him steady while the other called out, Fly, come on Louie, you can do it, Fly! Eventually we would gently push him off and he would open his beautiful white wings only to flap to the ground, a squawking, irritated flurry of feathers in the dust. Over and over Tim and I tried to teach Louie to fly. As time went on, with no noticeable improvement in his technique, I began to worry that if I failed to teach my duck to fly, I had failed as a mother. No one understood how important it was to me that I teach Louie something. Still, he followed me wherever I went in the yard, giving me my first experience of companionship.

In the middle of the summer Louie began to lay eggs; large, greenish, circles of life. I changed his name to Louise. Each morning I ran out to greet her, quacking as if I had joined the duck family rather than the other way around. Sitting cross-legged on the earth, I let her nibble my ear, talked with her about my day and then gently, respectfully, reached under her downy bottom to see if she had a present for me.

The first time I found a warm egg it felt like Christmas and my birthday and Mother’s Day all at once. I swelled with pride, as if I had laid the egg myself. Kissing Louise with great enthusiasm, I gave her food and water, ran across the yard, opening the screen door with my butt so as not to have to use my hands, and announced to my disinterested family.

Look, Louie, oops, I mean Louise, laid an egg! Isn’t it incredible?

Mom nodded her head, feigning interest, then put out her hand. Let’s make French Toast, she said.

No, I said to myself, No! I didn’t want to give my egg away. I held on to it tightly, stroking it tenderly, tears dropping onto the shiny surface. No.

I reluctantly handed over my treasure and retreated to a chair on the screened porch as she cracked the egg into a bowl, adding milk, salt and cinnamon, to make our traditional Saturday breakfast. I was so familiar with having my enthusiasm doused with cold water that I slipped away inside myself, no longer aware of the great pride I’d felt in my duck. I wanted my mother to see my excitement, to make a big deal out of this little miracle. I wanted to feel her warmth and embrace and understanding. I wanted her to know what was in my heart, and I had no words for this.

When the meal was served my normal healthy appetite was gone and I only picked at my food, eating the bacon dipped in maple syrup, and a small piece of melon, but avoiding the French toast altogether.

Two Steps Forward, Three Giant Steps Back

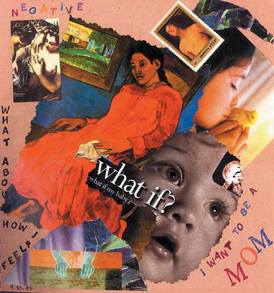

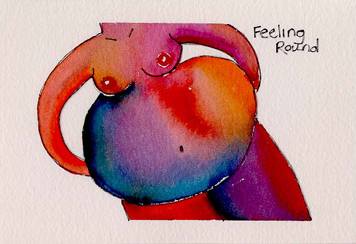

From that point on motherhood was part of my life itinerary. As though Baby was tattooed on the dance card of my life, I never doubted my desire to bear and raise children. Unlike many women I met in my teens and early twenties who weren’t at all sure about motherhood, I knew I was mother material. I gravitated toward children whenever they were present. I imagined the joy and magic of pregnancy. I wanted to know about natural childbirth and was determined to remain fully aware of my body during birth, no matter how intense the pain might be. I read books, watched movies and talked often about my obsession with motherhood.

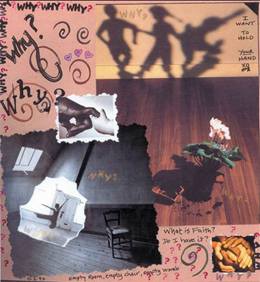

Why, then, was there such a startling incongruence between what I knew in my heart and the choices I actually made? Like living the life of a gypsy, unaware of how to plan for responsible parenting. Like having an obscene attraction to men who had no desire to have children. Like believing that all I had to do was want to be a mother and Presto it would happen. For the next twenty years, clock ticking away, I made choices that took me in the opposite direction of my dream. My mind may have been set on motherhood, but my actions screamed ambivalence.

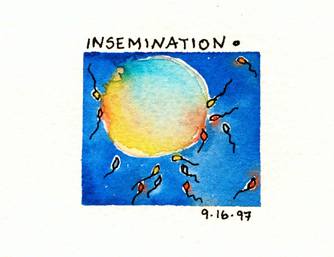

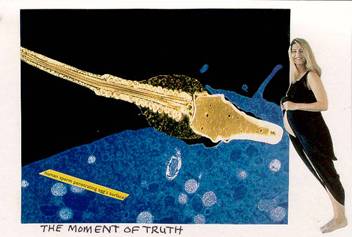

It took over twenty years to earn the title of mother, years of wrong turns, dead ends and misadventures, years of searching, in which all the affirmations, prayers, sweat lodges, therapy and mystical experiences actually kept me at a distance from what I wanted most. Once I understood that a baby comes from sperm meeting egg (of course I knew this, but forgot to actually do it while the sperm was there for the taking!), and that I could make this happen on my own if it was what I truly wanted, then the ball started rolling in my direction, and couldn’t be stopped.

Sign up for my newsletter, and I’ll keep you posted on the book’s progress, publication dates and book tours.

To see more images from the book, click here.